Sarah van Gelder: Could you tell me about your background?

Winona LaDuke: My father was Anishinaabe and my mother was a first-generation Russian/Polish Jew from New York. Both were involved with social movements—the Native American movement, farmworkers’ movement, poor people’s campaign, and the environmental movement.

I’m Bear Clan from the White Earth reservation, which is located between Bemidji and Fargo. My parents met because my dad was selling wild rice. I am part of a wild ricing culture. We are not rich in money, but we are wealthy in rice and other traditional foods. Sun Bear was my father’s name, and he used to have a saying: “I don’t want to hear your philosophy if it doesn’t grow corn.”

Sarah: You have focused much of your work on food and energy. What is your approach to these two basics?

Winona: Well first, we have to relocalize our economies. That doesn’t mean no imports and exports. But whether it’s food or energy, we’ve got to cut consumption; we’ve got to be responsible and efficient about what we use; and we’ve got to produce energy and food locally as much as you can.

There’s a phrase in Ojibwe, ji-misawaanvaming, which means something like positive window shopping for your future. We need to ask what our community is going to look like 50 or 100 years from now.

I’ve worked in my own community since 1981. We tried waiting for the federal and state government to take care of things, and if we had not taken action, we would still be waiting and I’d probably have a big ulcer from complaining, or kvetching as we say in Yiddish. We decided instead to put our hearts and minds together. We may not be the smartest, or the best looking, or the richest, but we are the people who live here. We decided we wanted to make decisions about the future of our community.

Sarah: What do your teachings tell you about creating that future?

Winona: We have a lot of teachings and language about how a people can live a thousand years in the same place and not destroy things. The phrase anishinaabe akiing, for example, means the land to which the people belong. It’s not the same thing as private property or even common property. It has to do with a relationship that a people has to a place—a relationship that reaffirms the sacredness of that place.

All our places are named. Near Thunder Bay, Ontario, is “The Place Where the Thunder Beings Rested on their Way from West to East.” We go there to do vision quests, to reaffirm our relationship with that power, and to offer our gifts to the thunder beings and the part they played in our creation. That place, and the places where our people stopped on their migration—all these places are named—and they have a resonance with us.

In all our teachings we understand that all the creatures are our relatives, whether they are muskrats or cranes—whether they have fins or wings or paws or feet. And in our covenant with the Creator, we understand that it is not about managing their behavior—it’s about managing ours, because we’re the ones who cause extinction of species. We’re the youngest species, and we don’t necessarily have the most smarts. We’ve bungled up along the way, and we acknowledge these mistakes in our stories and in our history as Indian people. The question is whether you have the humility and the commitment to get some learning out of these experiences.

Winona LaDuke. Photo by Harley Soltes for YES! Magazine

Sarah: What happens when this land ethic and this humility bump up against the dominant culture?

Winona: Ninety percent of the land on our reservation is held by non-Indian interests. We had the misfortune of having a neighbor who lived just to the south of us named Frederick Weyerhaeuser. We had fine white pine on our reservation, and he built his empire off of the land of the Ojibwe people in northern Minnesota.

And that is how some get rich and some get poor. It’s important to remember that most of these guys did not get rich by spinning flax into gold. They took someone else’s land, and they took someone else’s wealth.

That place known as The Place Where the Thunder Beings Rest isn’t called that now. It’s now called Mt. McKay. I don’t have a problem with Mr. McKay, but I do have a problem with this practice of naming large mountains after small men. How could we name something as immortal as a mountain after something as mortal as a human?

This could be fixed. Just look at Ayers Rock in Australia. It’s called Uluru now, because that’s its traditional name. Mt. McKinley in Alaska is now called Denali. The country of Rhodesia is now called Zimbabwe. It’s not disastrous to rename.

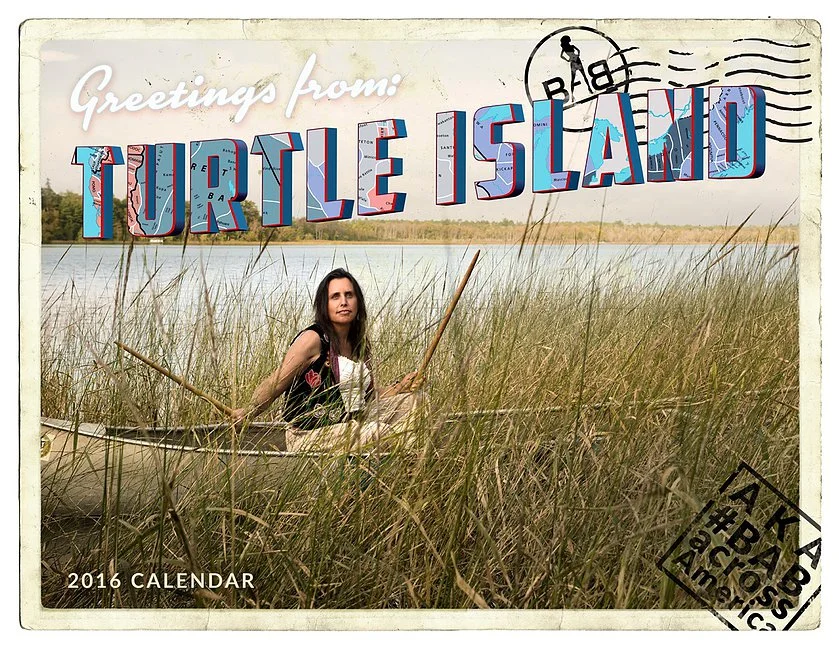

Sarah: Can you tell me about how wild rice is harvested?

Winona: We go up on the lake and we put our asemaa, our tobacco, on it. My son is my ricing partner, and we canoe through our rice beds. I used to push him, but he got too big, so now he pushes me out there, and I knock rice into the canoe with two sticks.

The rice grows on our lakes and rivers—some is fat and some skinny, some short, some tall. Some grows in muddy waters, some looks like a bottle brush, and some looks all punked out. That’s called biodiversity. It means not all the rice ripens at once. Some gets knocked off by wind. Some gets a blight, some doesn’t get a blight. The Irish potato famine should have taught us that agricultural monoculture is dangerous—but so is a social monoculture (or you could say, mall-culture).

The anthropologists used to come out and watch us manoominike—harvest the rice. After we rice in the morning, we bring our rice in and let it dry. We parch it over a fire, and we dance on it to get the hulls off, and then winnow it in a basket. We pretty much do the same thing today using wood fires as we’ve always done—we’re an intermediate technology people.

Ojibwe is a language of 8,000 verbs. The word for “work” is a strange construct for us. It doesn’t mean we aren’t a hard-working people, but in our language, the word is anokii, which means that whether you are fishing or weaving a basket, what you are doing is living—which is not the same thing as being paid a wage to do something.

After the harvest, we have a big feast, and we dance and tell stories. The anthropologists watched us, and they didn’t like that. They said we would never become civilized because we enjoyed our harvest too much. We did too much dancing, too much singing.

When you no longer enjoy your relationship to your food, to your plant relatives, to the harvest, to the dancing and singing—when you end up with a harvest that has no relationships or joy, I think that must be the mark of civilization and industrialized agriculture.

Sarah: What is the foundation for your economy? Do you sell your rice?

Winona: We sell our rice through Native Harvest. But for us, eating the rice is more valuable than selling it. Ensuring that our people have enough rice is what we’re after.

In our community, we don’t have a lot of wealthy people, but we have a lot of drums. We have a lot of songs. We have great maple syrup, harvested by hand and by horse, and boiled by wood. We are able to access the medicine chest of the Ojibwes. We have knowledge that is 10,000 years old. And we have the wealth of our relations to each other and to the natural world.

In our community, the stature of a human being is not associated with how stingy you are and how much you have in your bank account. It’s how much you give away, how generous you are.

It took the University of Minnesota about 40 years to figure out how to domesticate wild rice and cultivate it in rice paddies using chemicals and fertilizers, regulated so it could be harvested with a combine. They called it progress, declared it the state grain of Minnesota, and it took just a couple of years before Uncle Ben’s and the others took it over. Today, three quarters of all wild rice on the grocery shelf comes from giant rice paddies in California. No Ojibwe in sight.

Two Indians in a canoe can’t compete with a guy on a combine. One of my elders, Margaret Smith, and I went out to the lakeside because rice buyers were there trying to force the price they’d pay Indian people for rice down to 50 cents a pound. We said we’re going to pay a buck a pound. Margaret’s a good bluffer. They didn’t know how much money we had.

In 1986 we started fighting their right to call it “wild rice” because we think wild should mean something. In Minnesota you have to label rice as cultivated or wild, but in California or Oregon you can still sell cultivated rice as “wild” rice.

Our worst fears came true when the University of Minnesota cracked the DNA sequence of wild rice in the year 2000. They have not genetically engineered wild rice, but they want to reserve the right to do so. Our people do not believe that our sacred food should be genetically engineered, so we have been battling them for seven years.

Our foods are very much threatened, and this is an international issue for indigenous people.

After the harvest, we have a big feast, and we dance and tell stories. The anthropologists watched us, and they didn’t like that. They said we would never become civilized because we enjoyed our harvest too much.

Sarah: Besides protecting wild rice, what are you doing to bring back traditional foods?

Winona: We are growing more of our own food. About seven years ago, we got a handful of Bear Island flint corn from a seed bank and now we have about five acres of it. The corn is higher in amino acids, antioxidants, and fiber than anything we can buy in the store.

The traditional varieties of food that we grew as indigenous peoples—before they industrialized them and bred out much of the nutritional value—are the best answer to our diabetes. A third of our population is diabetic. We give elders and diabetic families traditional foods every month: buffalo meat, wild rice, hominy.

My 8-year-old, Gwekaanimad, and I started a pilot project with theschool lunch program after I saw that they were eating pre-packaged food from

Sodexho, Sysco, and Food Services of America. We try to give our school kids a buffalo a month and also some deer meat, some local pork, and local turkeys. We started growing and raising our own. It’s just a start. We had to de-colonize our kids, too, because they got used to thinking that their food was that other stuff.

We plowed 150 gardens last year on our reservation. I’m a big proponent of gardens, not lawns. It turns out in most reservation housing projects you can’t grow food. That spot in front of your house is where you park your car, or your dogs will trample it, or your cousin will drive over it. So we’re putting two-foot-tall grow boxes up there, and you can grow a lot of vegetables in them.

Our goal is to produce enough food for a thousand families in five years. And these foods we are growing in anishinaabe akiing are not addicted to petroleum, and they don’t require irrigation or all those inputs. These strong plant relatives just require songs and care for the soil. And in a time of climate destabilization, that is what you want to be growing. You don’t want to be guessing with some hybrid.

Sarah: What about relocalizing energy?

Winona: I’ve worked on energy issues pretty much my whole life. I’ve worked in Indian communities that are facing the biggest corporations in the world, and I’ve seen the effect of those corporations on land, people, and dignity.

Now, after 30 years fighting coal mines and uranium mines, to see the Bush Administration and Stewart Brand saying “nuclear power is the answer to climate change” I just feel that it’s time to move out of the box and into the next energy economy.

So now wind developers are coming into Indian country, which, it turns out, is rich with renewable potential.

Bob Gough from the Intertribal Council on Utility Policy says you’re either going to be “at the table” or you’re going to be “on the menu.” I want to see our Indian communities produce wind power on our own terms and own it. I want to see our young people benefit from it and train to be part of the next energy economy. We are a rural part of the Jobs not Jails movement that Van Jones and Majora Carter are leading in urban areas.

They say Native people in this country have the potential to produce one third of the present installed U.S. electrical capacity. When I first proposed a windmill on my reservation, members of the tribal council looked at me like I was nuts. But now one of my guys made me laugh, he said, “You know Winona, we used to think that you were crazy, but now we see that you were right. Someone had to stick their neck out!”

My tribe is putting up a 750 kilowatt wind turbine to power our tribal office building. Our organization put up a 250 kilowatt turbine. A tribe four lakes away has a lot of money, but not much wind; they asked us to site a two megawatt turbine for them on our reservation.

We are putting solar heating panels on the south side of our elders’ housing. It’s very simple technology; when the sun heats the panel up to about 90 degrees, the thermostat cranks on the blower fan, and blows hot air into your house. It works for us because even when it’s 20 below zero, the sun shines.

But we start with energy efficiency. I don’t support creating energy to feed an addict unless you deal with the addiction.

Sarah: What gives you hope to keep on with this work?

Winona: Life is good. We’ve been blessed with food that grows on water (wild rice) and sugar that comes from trees.

We’re technically one of the poorest counties in the state of Minnesota. My theory is, if we can do it, anybody can do it. It’s up to us—we’re making the future. If we’re waiting for somebody else to grow those gardens for us, well, we’re not high on their priority list. We have a shot at doing the right thing. So mino bimaadiziiwin (the good life), that’s the future we’re trying to create in our community.

Sarah van Gelder interviewed Winona LaDuke as part of A Just Foreign Policy, the Summer 2008 issue of YES! Magazine. Sarah is the Executive Editor of YES! Magazine.